Interracial adoption, also sometimes called transracial adoption, describes adoptive families where the child has a different ethnic background from the parents. About one third of adopted children have this type of family. 28% of adoptions are interracial, and more than half of non-white children are adopted by white families.

A study focusing on the Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994 (MEPA) found that transracial adoptions increased between 2005 and 2019, and Arkansas was one of the top five states to see this increase. Ion Arkansas, the number of interracial adoptions shot up from 181 to 650 by 2019.

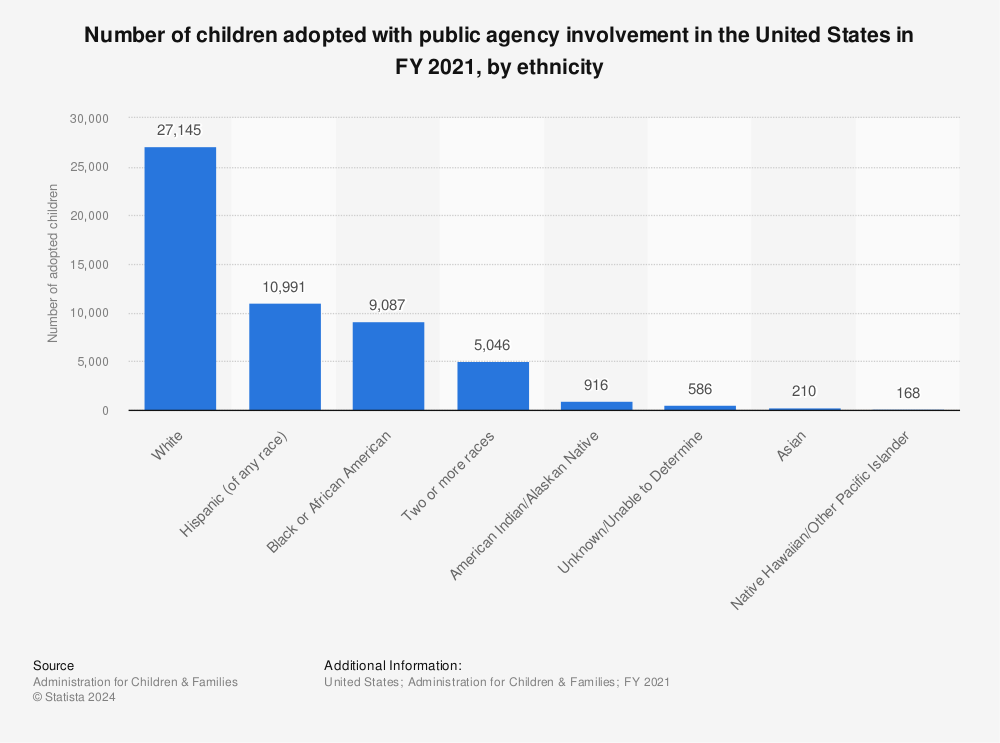

MEPA was put in place in order to help with a specific problem: among foster children, white children were adopted much more frequently than children of other ethnic backgrounds. The goal of MEPA was to help other children, and especially Black children, find adoptive homes faster. The increase in interracial adoptions showed that this goal was closer to being met. However, it continues to be easier for white children to be adopted than for children of other backgrounds.

The history

In the twentieth century, and especially during the Baby Boom years after World War II, adoptions were often treated as secrets. Adoptive parents might not even tell their children that they were adopted, and adoption agencies often did their best to match parents with children who resembled them physically. Since white parents adopted more frequently than people of other ethnic groups, fewer non-white children were adopted.

Native Americans had a different situation, since there are specific laws and processes encouraging adoption of Native American children within their local communities. Asian, Hispanic, and Black children were simply less likely to be adopted and more likely to end up staying in foster care. Black children spent an average of 33 months — nearly three years — in foster care before finding a permanent home, compared with just over two years for white children.

MEPA made it illegal for adoption agencies to refuse to place a child in an adoptive family on the basis of race or ethnicity. It also made it illegal to reject adoptive parents or foster parents on such grounds. In fact, agencies were required to make efforts to find diverse foster families.

Myths about interracial adoption

nterracial adoption, where adoptive parents and children come from different racial or ethnic backgrounds, can be accompanied by a range of misconceptions and myths. These myths can influence attitudes and policies regarding such adoptions. Here are some common myths:

- Myth: Interracial adoptions are problematic for children

Reality: Research shows that children in interracial families can thrive just as well as those in same-race families. The success of an adoption depends more on the quality of parenting and the emotional support provided than on the racial or ethnic match. - Myth: Children in interracial adoptions struggle with the identity

Reality: While children may face unique challenges related to their racial or ethnic identity, supportive parents who foster open conversations and connections with their child’s heritage can help them develop a strong, positive sense of self. - Myth: Interracial adoption is a form of cultural erasure

Reality: Effective interracial adoption involves actively preserving and celebrating the child’s cultural heritage. Many adoptive parents make efforts to integrate aspects of the child’s culture into their daily lives, including traditions, language, and community connections. - Myth: Children in interracial families are more likely to experience racism

Reality: While children in interracial families may encounter racism or prejudice, this is not an inevitable outcome. The experiences of racism are influenced by a range of factors, including the child’s community, family support, and the parents’ ability to advocate for and support their child.

Factors in interracial adoption

Adoptive parents choosing to grow their families with children from different ethnic backgrounds might want to consider how they will celebrate and include their child’s ethnic heritage in their lives. Living in a mixed family can be easier in a mixed community. That’s not a requirement, but it’s worth thinking about.

Be prepared to talk with your child about race and racism. These things exist in our society, and we probably should be prepared for these conversations even if we don’t have a diverse family. If you add a child of another race to your family, you must be prepared for those conversations.

However, the race of your child may not be the most important factor. Diverse families are increasingly common in the United States, in biological and in adoptive families. The blessing of a new baby or child in your home is one of the most wonderful experiences in life, and an interracial adoption could make it happen faster for you.

At Heimer Law, we have extensive experience with all kinds of adoptions. Contact us for a free consultation.

Inquiry Form